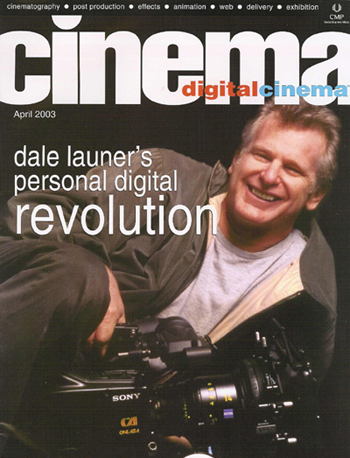

I should be happy, right? After all I've had tremendous success as a screenwriter in Hollywood. My first screenplay sale was not only produced, it became both a critical and financial hit: Ruthless People (1986). My second screenplay ended up giving me a precedent-setting deal (without the benefit of an agent!). This movie (Blind Date, 1987) also got made, which gave me another hit. I was two for two when a Mr. Mick Jagger and a Mr. David Bowie asked me to write a movie for them to star in. I suggested a remake of an older film, which ended up making without them. That was Dirty Rotten Scoundrels (1988), another hit, and I was three for three. Next movie? My Cousin Vinny (1992) -- once again, a critical and financial hit -- plus it won an Oscar for a then-unknown actress, Marisa Tomei.

Can it get any better? A couple years back I sold a spec script to DreamWorks for a cool three million bucks. I know what you're thinking: If that didn't make you happy, you got problems, buddy.

To be honest, the day a studio messenger brings over a $3 million check is a very, very good day indeed. So what's the downside?

There is downside if you can overlook a few things. For one, simply forget that the movie started out as your idea, with your characters. That you made every decision those characters make, that you created every word that comes out of their mouths. Every joke, quip, set-up, and pay off -- the entire plot in detail from beginning, to middle, to end. Just play along and pretend it's really their movie. And who are they?

They are the director. They will get the credit for everything you do. If you can accept that, then you'll have no problem as a successful writer in Hollywood.

Oh, and at the premiere? People will be crowding around you, getting you drinks, laughing at your jokes, and wanting to be your friend. That is, if you're the director. There will be no one swarming around the writer, unless it's your Aunt Rose -- and that's provided they let her on the list.

And that dinner after the premiere? The director will be at the table with the stars and the studio heads. You -- the writer -- will not be at that table. Nor at the adjacent table. In fact, you'll likely not even be at a table on the ground floor.

Nor will you be invited on the press junket. Even if you offer to pay your own way, you'll not be allowed to attend. The movie is made and you are not considered an asset.

And when you meet non-pros people not in entertainment business? They'll ask you: Exactly what is it you do? They believe the writer comes up with a vague story line and the director and actors come in and flesh it out.

But at least the money is good, right? Well, if your up-front deal is good, then -- yes -- it's as good as you can bargain.

But all those movies are hits -- you must be rich, right? That would imply that the writer of the screenplay actually participates in the riches of their hit film. And writers do get net profit, and they get a whopping five percent of it. But the term net profit is actually misleading, because it suggests you will get a profit based on the net income of that film. The trick is that the studios have something they tack onto your contract called a net profit definition. So, you see, net doesn't mean "net" and profit doesn't mean "profit"; they might as well call it transcendental carburetor because it makes about as much sense. If you were to add up five percent of the "net profits" of hit films like, oh say Ruthless People, Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, and My Cousin Vinny, you arrive to a grand total of....

Zero. 0. Zed. Zip. Nada. Bupkis. Dick.

You can try complaining and whining. I did; in fact all writers do it. The Writers' Guild of America has complained and whined about this for decades. Yet nothing has changed. You will eventually learn that whining is not a particularly efficacious practice. If you don't have a problem with any of this, then go write a hit movie, get it produced, and enjoy.

See, I could tell you even more stories, infuriating, insulting stories, enough to fill an entire book. But take my word for it -- I was fed up. Fed up enough to do something really drastic. How drastic? Like make my own movies out of pocket. That way I could: (1.) make whatever I wanted; (2.) have total creative control; (3.) get full credit (or blame); and (4.) make a real profit.

There is no other solution. There is not other way. I was tired of whining, blaming others. This was time to take action. Put-up or shut-up time, and I was ready to put up.

Modified Dogme The Two-Point Rule. This started out as the One-Point Rule, that the screenplay was all-important. Writing some hit movies taught me one very valuable lesson: the all encompassing importance of story. The three most important ingredients to a movie? Screenplay, screenplay, screenplay. A director can easily botch a moment, but they have to work really hard to completely botch a moment. And a well-written character can even make a bad actor look good.

Wait. No, that isn't true. A well-written character can't make a bad actor look good, it can't even make a mediocre actor look good. Better maybe, but good writing simply can't make it past a bad actor. They don't understand what they're saying or why they're saying it, they'll emphasize the wrong words -- oh, there are many, many ways a mediocre actor can ruin a project. So the One-Point Rule becames...the Two-Point Rule -- screenplay and performance.

So, my thinking was -- if the screenplay was sound and the performances work -- it would carry the movie across an abyss of mediocrity. You could shoot a movie on a home video camera -- and if it's in focus and the story and performance are there -- it should work, right? Sure, you need some basic levels of competency and craft, but all the craft in the world won't allow you to squeeze a good film out of a rotten script.

I'm trying to make a point here because I can't afford to make a movie the way movies are made in Hollywood. I don't have millions of dollars to spend. I don't even have a million. (Taxes and mortgages ate into that 3 mil pretty quickly). I'd have to go low budget. Very low. How low can you go? Well, you know that idea about make a movie with a home movie camera? I'd heard someone made one and it was showing locally.

It was called The Celebration, an early Dogme 95 project that was shot with available light on a consumer-grade digital video camera (then blown up to film). I couldn't wait to see how my little theory turned out. The movie started and...it looked awful! Noisy, grainy, and it had an overall mushiness of the image, with bland-looking color, and some kind of weird motion stuttering. It was just painful. For the first third. And then the drama kicked in, the story moved into second gear, and holy cow! -- The Two-Point Rule stepped in and just took over! The grain, the mushiness, the color, everything suddenly "went away." I was caught up in the story and the characters.

Still, could I make a movie like that? A movie that looked that bad? Despite all that carping about the Two-Point Rule, could I be happy making a movie that look awful? After all, I've been getting American Cinematographer for nearly 30 years now. I got ZOOM magazine when it first came out. I love great cinematography; I think Vittorio Storaro is a god and have felt this way since 1970, when The Conformist single-handedly changed the look of motion pictures. And then there's all those great film noir pictures.

Sure, I love great cinematography, but I've never seen a bad script made into a great movie because it had great lighting. I see gorgeous bad movies all the time. And I've seen some great movies with mediocre, uninspired lighting.

So, I was struggling with a conundrum. That bad-look thing just stuck in my craw and it wouldn't budge. The solution came to me in two parts.

For one, the lighting in The Celebration looked pretty good, and that was "available" light. So what if you made a movie like that, but on film? On 35mm film? Or Super 16mm? No grain issues, no mushiness, no bland color.

I ran the idea past some cinematographers and they all hated it. And they all had the same arguments: light changes during the day, what if you're stuck in a room with white walls, etc? But they all ended up mentioning Sven Nyquist, a legendary Swedish cinematographer who worked with a lot of natural light and produced some simply gorgeous work (Siddartha). Ridley Scott's first film The Duelists looked great and took serious advantage of natural light. And all the cinematographers mentioned that some of their most beautiful work was done with available, natural light.

And man, would it save money! See, if you're not lighting a movie, you're not renting that lighting kit, and you're not renting the truck to haul around the lighting kit, and you're not paying the teamster to drive the truck.

And while you're not waiting, you're shooting, meaning you make the movie in a fraction of the time -- less than half the time of a normal shoot. The costs just drop. The Screen Actors Guild, the Writer's Guild, and the Director's Guild all have low-budget provisions -- the cheaper the budget, the less you have to pay. The script I had in mind had two actors and a dozen day players. I could make a movie out of pocket -- and own it. Have total control! And profits! Gross profits!

I'm not saying that you should go willy-nilly onto location, start shooting the movie, and damn the lighting. You must choose your locations with light in mind, nix rooms with white walls, or rooms without windows, and you shoot where the light is good. Put the actors where the light looks good. No, it wouldn't have a specific, designed, consistent glossy look. It would be natural and simple. And it could actually look pretty. And I could afford it.

Choosing Gear I started doing some research and discovered Sony's digital high-definition HDW-F900 camera. It was designed for digital movie making in that it offered progressive capture (yielding a sharper image and eliminating that "jittery" strobing issue). It had a film-style 16:9 aspect ratio, and would shoot 24 frames per second. It promised to look much more like film than any other video camera available. And the color sampling was superior to DV.

I went to NAB, saw the camera, saw the results, and I was in. I hooked up with Sony rep Todd Kirkendall, who later took me to Band Pro, a major Hollywood motion-picture camera and equipment dealer, to meet with technical officer Michael Bravin. I put in an order for an F900. The camera arrived six months later, and I also bought some batteries, a charger, an Angenieux 5.3-53mm HD zoom lens, and other goodies, including a little color monitor, Sony's BVM-D9, and an ERG LCD on-camera monitor. Oh, and some tapes. One last thing and I was ready to go; I put together an editing rig that allowed me to edit in HD uncompressed. The rig included an Apple G4, a Pinnacle CineWave card (with HD breakout box), three Huge Systems DualMax 1200 arrays, and of course the ubiquitous Apple Final Cut Pro.

TRIAL RUN

Of course, I had to learn how to use the camera and the editing gear. I need to shoot something and put it together. So, partially as grist for the mill, and partly as a proof of concept, I wrote a ten-page, ten-minute short with the idea of shooting it -- all of it -- in one day. Since the average feature shoots 3.5 pages a day -- this would be particularly ambitious. More so since I wanted to try out shooting with as small a crew as possible -- three in all. One crew member was Andrew Chiaramonte -- another filmmaker on the digital bandwagon I'd met through Michael Bravin at Band Pro. We also had a focus-puller who was curious about HD video. But I was avoiding shallow-focus shots; it's just another thing that can go wrong. But we did need a sound man and that's what he did.

I also used this opportunity to try out some other ideas. For one, I would not have a shot list. Instead of forcing the production to carry out a list of preconceived shots, I'd just wing it. This was hard for me, but I know if you have a shot list, you tend to stick to it, when you might be off rolling with the punches. And if the film turned out well, then I wouldn't feel that sense of panic when I had to face whatever weird kink Murphy's Law might serve up that day. The story would carry it thru. The worst that could happen is a total disaster, which means a day of work is lost. I've lost years to development executives; this kind of failure would be cheap by comparison.

I used a couple friends to play the leads, both professional actresses, and both well-suited to the roles I had written. They would be responsible for their own make-up and wardrobe.

It was a surprisingly grueling shoot. I had a 3:00 p.m. call, but we didn't get our first shot off for a good two hours. At NAB the camera on my shoulder seemed so effortless -- I thought I could keep it there all day. Not so. When you're watching actors, and shooting, and framing, and thinking about this and that, the workload (and camera weight) seems to jump up exponentially.

Also, when you're not setting up lights, you don't have any time to think about the next shot. Or the one after that. There was no air-conditioned trailer for me to curl up in with a pen and yellow pad to tinker away at a shot list. When you're shooting that fast, there's simply no time to think. And when the shot is done, you have the crew looking at you -- staring at you -- while you make your next decision. There is this tremendous momentum. For me it made directing actors that much harder. On a normal set, when you're looking at a monitor 20 feet away from the action, you're distanced enough to focus on performance.

It turned out to be a terrific learning experience. And it was fraught with problems. Nothing disastrous, but nearly so. Whatever mistakes I made on this, I wouldn't make on the feature shoot.

For instance, the sound was screwed up in a few places. We didn't have a professional working the sound mixer, but we would on the feature. When the movie was cut together and was shown it worked surprinsingly well and looked pretty good. Pretty good. No bad.

But it could have looked better. I would use a shot list, but I knew if I didn't and just did boring standard stuff -- it still worked. That that story and performance could carry it. Nevertheless, while working on the fly, shooting and directing, it was hard for me to remember choices that should have been obvious. So why not just have an operator/DP who's thinking about composition, or where pretty light is, camera angles, the lens choices, and consistent exposure? That would be money well-spent.

And instead of shooting ten pages a day, we would shoot a "leisurely" seven. It would be a three-week shoot.

The screenplay would be Tom's Nu Heaven, a dark comedy about a Catholic priest and his brother driving cross-country. It's been described as a Kierkegaardian Road Trip.

Crewing The crew size grew from three to five immediately. I would have a DP/operator, who'd get an intern. One sound man, with an intern on boom.

I was willing to modify the "available light" rule -- why be a nazi about it? I didn't intend on making a Dogme film, I just didn't want to wait for lights to be set up. Or rent those lights, or the truck....

I wanted to shoot in the spring, but casting (our two leads were Sean O'Bryan and Craig Sheffer) took longer than expected, which delayed the production, and then my leading man took another film, which wouldn't have him back in the country until the summer. I didn't want to re-schedule for the fall. We would be shooting in July. I'm gonna sweat.

I had a guest house we would use as a production office -- a couple of desks, a fax machine, and a few phones.

My original DP kept his schedule open, but the delays were costing him money (married, with a family), so he dropped out for a better-paying job. I would take the role of line producer, UPM, and 1st AD, and roll it into one job. A tough job since we'd being doing it with DGA, WGA, and SAG talent. Lotsa contracts and lotsa rules! But having all those roles in one person is like one-stop shopping. I hired "Oak" O'Connor." At 6'5" Oak is appropriately named; he's tall and kinda scary-looking. I knew if we had problems -- say someone wanted to back out of a deal -- "Oak" could "sweet talk" them.

It was a few weeks prior to the shoot and we still didn't have a DP. I'd met David Mullen at Cinegear Expo and he had much practical experience shooting HD. If fact he shot one of the first (maybe the first) HD features, Jackpot, which had a nice, natural look. We had originally met online thru CML, a cinematography site, where I found his posts refreshingly literate, intelligent, and reasonable. He was interested. He read the script, thought it was funny, and had no problem with the "rules." I let him know I was more that willing to put the actors anywhere the light looked good, and that he could veto any location that didn't have decent light. He asked to have a Kino-Flo light or two. He was in.

Preproduction The script seemed simple; two characters on a road trip, mostly in hotels, on the road, or in restaurants and a few bars. But there other, more challenging locations -- like a Catholic church. This was a very provocative movie, and no way would any church sign off on it. And we needed a hospital. Oh, and a prison, and a parole board conference room. And there's a scene in a police station. And a doctor's office. A soup kitchen. A classroom. A confessional. And we had almost no money for locations.

Well, enter the old Herald Examiner newspaper building in downtown Los Angeles. It was a large building that had a dozen or so "ready-to-wear" movie sets -- all dressed and ready to shoot, including: two newsrooms (period and contemporary), two police stations (period and contemporary), a courtroom, a morgue, a bar, a hospital, a few "offices" -- everything but a church. But the lobby was so ornate (designed by Julia Morgan, designer of Hearst Castle) that when filled with pews (borrowed from the courtroom set across the hall) at the right angle -- with a podium and a crucifix -- it looked very church-like.

Oak had a lot of de facto low-budget production experience, whereas my experience (before my Hollywood career), was more along the lines of no-budget. (That's another story, about a one-man feature shoot, in 35mm film!). Though I was the director, I was also paying for the movie. I was always arguing for smaller and cheaper, and he was caught in the unusual position of trying to grow the production rather than shrink it. Oak strongly recommended David Morong as our production designer. We met and immediately hit it off. He was smart and would be fun to work with. All department heads would get intern/assistants.

The size of the crew slowly increased. I didn't think we'd need craft-service; just let an intern load up some coolers with soda and snacks. But we would get one anyway. By the way, but Trader Joe's is a perfect craft-service shop.

We also hired one all-around grip, someone with experience. Could we trust a cube truck filled with gear to an 18 year old? No, so we hired Ben Hernandez, a hard-working driver/grip/do-anything (including blues harp) guy.

We even hired wardrobe, who got an (intern) assistant who would be near the set at all times. The boss would come on days when needed. It worked out as kind of a hybrid professional/student film. All department heads were seasoned pros, and each had an intern. Interns work hard, learn fast, you get 'em cheap, and they're grateful for the opportunity.

And it turned out to be a very workable situation.

My experience with interns is that they have a way of not showing up after a few days. That's largely because they're asked to work hard with no pay, which is humiliating. So I ponied up to pay a whopping minimum wage to the interns. No, they wouldn't get rich, but if I were in film school, I would have loved to have been on a shoot like this. And get a check. Better'n working at Burger King.

Our budget was low enough that we probably could have wrangled SAG to work for "free" by exploiting their definition of experimental film. But that would be abusing the actors themselves. The next jump up was $100 a day -- and that still wasn't enough. So we went to the next step up -- which was over $200 a day -- enough to show up and not feel humiliated or exploited. (Our leads got more than that.)

Oh, and did I say that all department heads (and some of the interns) would get a piece of the real net profit? No bogus "definition"; the words mean what they say. Let this sink in: They get a more favorable profit participation than any "A" list screenwriter and most "A" list directors. Oddly enough, the term net profit has been so maligned in Hollywood that many of the participants (who've never seen any kind of profit participation in their contracts) dismissed it outright, convinced they'll never see "net profits." I hope to get my revenge when they get their first checks. Oh, the humiliation!

Small crew, modicum of pay for everyone, real profit participation. This is how it should be. Now to shoot that movie.

Band Pro, meanwhile, had a set of prototype Zeiss DigiPrimes, hands-down the best lenses for HD on the face of the earth. And they offered them to us to use. These are dream lenses; designed to be at their maximum resolution when wide open. And they're fast, sharp, pretty, and compact, which means they could be used for hand-held work. Also, Zeiss had this very nifty "Carl Zeiss Sharp Max," a collimation device designed to provide accurate and consistent back-focus. This would put my back-focus anxiety on the back burner.

Production Begins The first day had us in the Herald Examiner building, where we shot (get this): an exterior prison scene, an exterior police-station scene, an interior prison scene, two interior parole-board scenes, an interior hospital scene, a montage shot in a prison cell, and a bar scene where Craig Sheffer's character tries to bum a drink and gets kicked out.

The biggest drawback was the heat in the Herald in July. It was a hot box. For someone who feared heat it was a reverse descent into Dante's Inferno. The higher you got, the hotter it got. And it got hot. No equipment problems, but the actors were always dripping with sweat. I had fears it would be awful in editing. The craft service table (which I had mildly fought) turned out to be a must-have (for the endless cold sodas alone).

Now this was a semi-pro production. I'm not the first to do this, but this was my first time. We did have a few silly growing pains that seemed to work themselves out. On the Internet site CML, I had heard lots of rumor and innuendo. There is the back-focus issues that had been haunting the Sony camera; the problem is when there's is a ten-degree rise in temperature between the time you set the back-focus and you shoot, there can be a visible change. Solution? We turned the camera on the moment we arrived on the set, and kept it on all day. That was easy.

About half way into the first day, the on-screen confirmation message for the white balance (on the camera) seemed to shut down. But we had a reasonably color-correct Sony BVM-D color monitor. David flipped the temperature wheel until the color looked good -- and that was it. He would ask me to do check it with him. And I think I might have flipped through the wheels, and came to the same setting as David.

With a miniscule budget you have to give up any ideas about a specific vision. It makes more sense to empower everyone, and let them get creative within the narrow confines. And it worked great.

And HD video is just a dream to work with. David had a light meter, but I mostly remember him lighting it by eye with an occasional glance at the Sony monitor. I'd say roughly half the footage was shot without additional lights, about 45 percent with a solitary Kino-Flo, and the remaining five percent with a few lights (bar scenes). Practicals were always used, but bulbs were often changed.

Challenges and Solutions Toward the end of the shoot, we did the dream sequences at Craig's house, which is on Malibu Lake. We had one shot scheduled that put us outside -- a shot of two characters sitting at the lake. At night. We had planned to do a day-for-night and shoot it with the sun directly ahead of us but above the frame. The background would be mountains, and the sun would be reflecting off the water and silhouetting our actors, as if in moonlight. In post I'd planned to crank up the blue and tweak it until we'd only see the silhouettes.

Not wanting to disturb the neighbors, but still needing to get the shot with the two actors on the lake, we decided to use the long end of the zoom and shot out the window from inside the house. David wasn't happy about that; to make it work, the scene really needed to be directly backlit by the sun (which was up high out of the shot). In fact it was off to the side about 45 degrees. David went into the camera's paintbox, twiddled with the gamma and the color, and Voila! We got it. It looks great and it was a trick. Digital movie making is really fun when you make a tech trick work.

Another digital trick came into play a few times. We had a lot of footage in a car, but we had no car mounts or Shot-Maker to sit on to tow the "hero" car around. In fact there were no shots from the front -- we just sat in the backseat, getting a two-shot and singles. But I was aching for another angle, specifically something from the front. David suggested he sit in the passenger seat, camera on lap, and shoot up to the driver. We can shoot the "passenger" actor in the same way: have him driving, but keep the steering wheel out of the shot. We'd just flip it over in post. There is no reason for this not to work (unless you're passing a truck with lettering on the side, or billboards, or anything with print that's in focus). The CineWave editing rig is uncompressed HD, and digital flips are lossless and perfect -- bingo!

We did it again on the last night of the shoot. A exterior night shot, a two shot with singles. At 4 a.m., we were all tired, and we still had another scene (with a location move) to do. We shot the two-shot, and a single, but instead of breaking down the lights to light the other actor, David changed a light in the background, we swapped the actor's positions and shot. It is so sneaky!

The car scenes from the grid were just awful in editing; I had to break down the takes into beginning, middle, end, and how burned-out the light was in the background. Could we see blue skies? Light-blue skies? Burned-out skies? It depended on the length of the grid you were on. A day later we shot another road scene, but this time the run was long enough for the entire take, and then we'd flip the car around, but the view changed all the time. That's okay if you're cutting single to single. But if you want to cut from single to two-shot -- it has to match. And that's why you want to shoot on those long desert roads that disappear into infinity. It doesn't just look cool, it's easy on the editor. I should've known better.

It's a Wrap I started editing and found all the issues that worried me weren't all bad. Those sweating actors? Worked perfectly in the scene, like when Sean is on the floor in pain, the sweat just added to the situation, or when Craig emerges from a bathroom with a drip of sweat on his temple, his character had just washed his face and it looked like he missed a spot. No problem.

And the idea of flipping those shots over? Worked great.

We'll probably end up doing ADR on some of the car scenes. If I had to do it over, I'd still leave the AC on, but leave it low -- and keep it at one setting.

And when it was all cut together, despite the color matching by eye, the color was never an issue. In fact, I showed it to a DP friend who thought it looked better than most first answer prints! And that was without a lick of color correction!

I admit, having a caterer was a good idea, and this guy turned out to be very good -- terrific, considering the price. I'll use him again.

And despite my original intentions to run with a smaller crew, this still was a pretty a small crew. Even though we a liberal use of interns, it more or less felt like a real movie set -- sans a few dozen people, half a dozen semis, motor homes, and millions of dollars.

I'd do it again in a heartbeat. Maybe a few more interns, and a little more money for locations. I find the momentum and speed a little daunting.

All in all, it turned out looking even better than I thought. Getting a good look was partly about putting the players where the light was good, but largely about putting the camera in the right place; using side light or back light. It is a simple, natural look, and surprisingly pretty.

To me, high definition digital video means you make a movie on the cheap without a cheap look. But the mere fact I can make a movie, that looks like a movie and works as a movie is very empowering.

So if you're willing to "roll your own," and you want it to look professional -- and use SAG, WGA, and DGA talent -- the price of admission is fairly reasonable; for me it was a little over $100,000.

Entrance * Press * California Living Piece * Premiere Magazine Article * Digital Cinema Article * Bio * Short Dale Launer Bio * Long Dale Launer Bio * Pics * Tom's Nu Heaven Movie Stills * Pictures of Dale * Flicks * Toms Nu Heaven Trailer * Filmography * Words * Creative Hints and Cheats for Writers * The Simple Cure to Writer's Block * National Association of Broadcasters Speech * Response to NAB * Guestbook * Contact * Sitemap * Links

© Copyright 2004 dalelauner.com